In Round 12 of the 1953 season, Balmain's Bobby Lulham had a great game. The winger scored all of his team's 13 points in their win over Manly at Brookvale Oval. A week later they rolled St George 26-12, with Lulham – who had played for Australia and was part of the NSW team during that infamous 1947 trip to Brisbane – scoring 17 of his team's points.

But he had a shocker in the next game against Canterbury. He didn't score a point in the 14-7 loss, and was slow across the field, regularly getting smashed by opponents before he could pass the ball. Lulham's performance was so poor he was hooted by the Leichhardt Oval crowd.

He knew he wasn't right, complaining of a heavy feeling in his legs before the game. But he took the field anyway, not wanting to let down his teammates. On Monday, 20 July – two days after the game – he went to his job as a truck driver but collapsed and went home sick. Two days later he would discover the reason why – and it would create quite a scandal, easily on par with anything the modern-day footballer can come up with.

Lulham was suffering the effects of thallium poisoning. Marketed as rat poison Thall-rat and bought by many households, thallium was involved in a spate of poisonings in Sydney in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Between March 1952 and May 1953, there were 46 reported cases of poisoning, many of which were attempts to murder a person. Indeed of those 46 cases, 10 ended in death.

On the Tuesday night, Lulham was admitted to the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital with symptoms of thallium poisoning – limb numbness and hair falling out. The penny had dropped when NSWRL medical officer Dr Greenberg got a call on Monday from a woman saying her husband had put rat poison in Luhlam's beer while he was drinking at the pub.

The doctor then called the club, who told him that Lulham was suffering from the flu. So Greenberg put it out of his mind until the next day when he discovered Lulham was seriously ill and called the police. On Wednesday, the woman twice rang the police saying Lulham had been poisoned but would not give her name.

The Balmain winger himself was at a loss to help police track down his poisoner. ‘I haven't an enemy in the world that I know of,' he said. ‘I just haven't a clue. It has me beaten. I have thought and thought about it night and day, but have no idea who could have done it.'

His father-in-law Alf Monty, however, had a theory – it had been done in the dressing rooms after a game. ‘Anybody can walk into the players' dressing room at suburban grounds,' he said. ‘It is not uncommon for players to be handed a glass of beer by enthusiastic fans and it would be possible for a spectator – one who perhaps lost money on the game – to slap him on the back and say, “You played a great game. Here, have a beer”.'

A few weeks later, on 6 August, police made a surprising arrest – Luhlam's 45-year-old mother-in-law Veronica Monty. The police charged her with the attempted murder of Lulham, alleging she secretly gave him the thallium some time in early July. After being bailed out of jail, two days later Monty herself was in hospital, also suffering from thallium poisoning.

She would end up in the same hospital as Lulham, who was eventually discharged on 19 August. Several weeks later he took part in Monty's committal hearing to see if there was enough evidence to send her to trial. Lulham must have been dreading that moment, knowing what was likely to come out. If the people of Sydney thought the attempted poisoning of a rugby league player was a great story, it was about to get a whole lot juicier.

During interviews with Monty, police claimed she told them she had been intimate with Lulham on several occasions while living in the house with him and his wife Judith (Monty was separated from husband Alf). She also said she suspected Lulham of playing around, claiming she had found lipstick and make-up on his shirt. Despite that, when asked whether she was in love with her 26-year-old son-in-law, police said she told them ‘I like him very much'.

Regarding the attempted murder of Lulham, Monty said the thallium was intended for her. Feeling depressed she made herself a hot milk drink, mixing in some thallium. When Judith and Bobby asked if she could make them one each she did so. She claimed she got the glasses mixed up and gave Bobby the one with the poison.

Police also alleged Monty was the woman who had called several times claiming to know who poisoned him. She later said the calls were made as a way to ensure Lulham got the medical help he needed.

The court heard that one of the times Monty and Lulham had been intimate was while they sat on the lounge listening to the second Ashes cricket Test. She had raised concerns about Judith's happiness in the marriage and Lulham, believing there was nothing wrong, suggested he would go and wake up his wife and ask her.

Monty insisted he shouldn't do that, instead he should stay on the lounge with her. Soon thereafter, there was some passionate kissing. ‘I think we both stretched out on the lounge and got comfortable,' Lulham said. ‘After several kisses we became a little familiar with one another. There was no intercourse or anything like that.' Indeed, while police alleged Monty admitted intercourse had indeed taken place, both of them would later insist they never went all the way.

The pair also got together while Judith was away at Mass on a Sunday morning and again on that Monday when Lulham came home sick from work. Lulham told the court Monty had entered his bedroom and sat on his bed. She then removed her underwear, lay down beside him and ‘a similar incident occurred' is how a no-doubt embarrassed Lulham phrased it.

Despite the marital mess, Lulham maintained that Monty would never have tried to murder him, noting that she prepared the meals at home and so would have had ample opportunities to poison him if she wanted to.

The judge decided there was enough evidence to send Monty's case to trial. While waiting for the December trial, Monty and her daughter would live at the home in Ryde, while Lulham headed to the North Coast.

The trial captured the attention of Sydney with a long line of women queuing up at the courtroom doors armed with a packed lunch waiting to be let in each morning. The key players all had to parade their domestic secrets in public again, Lulham adding the detail that things never went further than a ‘petting party' despite the fact that clothing was removed or rearranged. It was also revealed that he had a pet name for Monty – ‘Tops' – and that he kissed her every day when he left for work and when he arrived back home.

Facing two charges – attempted murder and maliciously administering a poison – Monty pleaded not guilty to both. On the night in question, she said she had meant to take the poison herself and spent some time waiting for the results but to no avail.

‘But I was in for a rude awakening because what seemed like an apparently simple illness on Bobby's part developed, and the stark horror of it struck me – that Bobby must have got what I intended for myself.' At that point she couldn't come clean because people ‘would have thought the worst of me' for trying to commit suicide. So she instead made a number of phone calls saying Lulham was poisoned to make sure he got the medical attention he needed.

Monty escaped a jail sentence, being found not guilty on both charges. She celebrated the verdict with friends at Como; estranged husband Alf and daughter Judith were also there. Lest those celebrations suggest there was some level of forgiveness of Veronica, double divorces were on their way.

A week later, Alf made their separation permanent, while Judith decided to end her marriage to the man she had been with since she was 15. In granting both divorces, Justice Dovey decided not to go through the ‘nauseating details of the disgusting incidents' of the affair.

‘I am satisfied that Lulham did not initiate the intimacies on any occasion,' he said. ‘I am convinced he was seduced into participation in what has been quite properly described as scandalous conduct, and has been seduced into that position by the woman charged.

‘She may be properly criticised for breaking the marriage, which showed such promise, of having all that could be desired.'

Monty decided to sell her story to the Sydney Truth. While the front page of the 13 December issue carried the news of the double divorce, Veronica Mabel Monty told her story in a twopage spread, under the headline ‘I betrayed my own daughter'. Apparently having not had her fill of airing dirty laundry in public, Monty kept going.

‘My real heartache is for my daughter,' she wrote. ‘No one will know the agonies I have suffered in the knowledge that it was I who wrecked her married happiness. I feel I must go away where people don't know me and give Judy a chance to forget the wrongs she has suffered.'

Those who were hoping for more salacious details of what she and Bobby got up to would be disappointed. There was nothing new in her story and she only mentioned the night on the lounge listening to the cricket. She claimed ‘some kind of dreadful loneliness drove me into the arms of my son-in-law. There is no doubt I loved him deeply. But I must have been mad to show it.'

Regarding the purchase of thallium, she said she had no need for it and was not thinking clearly when she bought it. ‘My mind was in torment and I seemed to be losing control. I began to develop suicidal tendencies.'

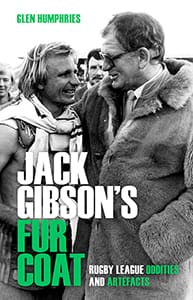

This is an edited extract from Jack Gibson's Fur Coat by Glen Humphries (Gelding Street Press $29.99) available at Big W and all good bookstores.

People look back at the fifties and criticise the time as being one of censorious narrow-mindedness and generally disparage it.

I wonder what would happen these days if the NRL found a player in a comparable circumstance. Would they stand him down ? Would they accuse him of bringing the game into disrepute?

Would social media take him to task? Would the #MeToo crowd give him a moment’s peace?

Apart from the technology, is society really that different, in how it talks about and criticise people whose behaviour does not fit with contemporary views of what is acceptable?

I’m not making a point, just reflecting and asking a question.